Celebrating and Remembering Juneteenth

Juneteenth arrives this year as demonstrations continue in the streets of the United States, protesting systemic racism and the killing of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis. For nearly two decades, the National Juneteenth Observance Foundation has been advocating for the date of June 19 (hence, Juneteenth) to be recognized as an annual national observance. But what is Juneteenth? And what does it have to do with California history?

The origin of Juneteenth can be found in the emancipation of enslaved African Americans during the Civil War, specifically in Texas, a slave state and the far western frontier of the Confederacy. As historian Quintard Taylor has noted, emancipation wasn’t comprised of a single event – like the promulgation of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, or the 1865 passage of the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery – but occurred in various ways. Traveling with the people who claimed to own them, hundreds of enslaved people journeyed to California during the gold rush. Once in the state, some paid for manumission papers with money they earned, others fled their enslavers. Across the U.S. during the Civil War, the constant flood of refugees from slavery increased dramatically, and forced the U.S. military to confront the “contraband property” laws that required officers to return people who escaped to the slave holders U.S. troops were battling. Congress passed laws, including the 1861 Confiscation Act and the Act Prohibiting the Return of Slaves in 1862, that culminated in President Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation freeing enslaved people in former Confederate territory held by Union armed forces.

The Emancipation Proclamation was a turning point in the Civil War. Implicit in the President’s order was the recognition that black people had liberated themselves by fleeing slavery, and that it was up to the U.S. government to act. Their flight amounted to what scholar W.E.B DuBois called a “general strike” and Lincoln realized its potential. The proclamation gave the U.S. the military means to win the war, by depriving the South of its source of labor, and granting African Americans the right to join the military in a time when white enlistment was low and draft riots swept the North. Gradually, as the Union military reclaimed sites throughout the South, emancipation followed, through 1865 when Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered in April 1865.

But not in Texas.

The history of Texas is tied inextricably with California. Both states were born out of the politics of slavery. California was admitted to the Union as part of Congress’ Compromise of 1850 – a continuation of the doomed effort to balance political interests of pro-slavery members and those opposed to the expansion of slavery. As a result of the Compromise, California was allowed to be a “free” state; Texas remained a slave state and relinquished land in exchange for payment of its debt; public slave markets (though not slavery) were outlawed in Washington, D.C., and; the draconian, overhauled Fugitive Slave Law was unleashed.

The history of Texas is tied inextricably with California. Both states were born out of the politics of slavery. California was admitted to the Union as part of Congress’ Compromise of 1850 – a continuation of the doomed effort to balance political interests of pro-slavery members and those opposed to the expansion of slavery. As a result of the Compromise, California was allowed to be a “free” state; Texas remained a slave state and relinquished land in exchange for payment of its debt; public slave markets (though not slavery) were outlawed in Washington, D.C., and; the draconian, overhauled Fugitive Slave Law was unleashed.

From its inception, Texas was a slave state, and California, though “free” also experienced, in the words of one historian, “a remarkable continuance of slavery” until the end of the Civil War. Evidence of slavery in California abounds; in newspaper ads for slave auctions, manumission documents in court records, testimonies by anti-slavery activists, and newspaper stories covering plaintiffs suing for freedom. Slaveholders and their supporters, like California’s first governor, Peter Burnett, wielded power in and through the state’s public institutions, from the legislature, to the courts, and schools. John Carr, who arrived in 1850, observed in his memoir Pioneer Days in California, that “From 1849 to 1861, the State of California was…as intensely Southern as Mississippi or any of the other fire-eating States.”

Far from the battlefields of the Southeastern U.S., Texas was seen as a haven for slave holders, who migrated there, bringing enslaved people in the thousands, especially during the Civil War. At the end of the war, as the U.S. military took back control of the former Confederacy, many slaveholding Texans simply carried on, feeling protected by their remoteness. Major General Gordon Granger became commander of Texas with the charge of putting down the rebellion. In Galveston, on June 19, 1865, three months after Lee’s surrender, Granger proclaimed his general order informing all citizens of Texas that “all slaves are free” with “an absolute equality of rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection therefore existing between them becomes that between employer and free laborer.” Granger’s order was directed primarily at whites who continued to coerce black labor, but it was African Americans who chose the day of his order as an opportunity to celebrate freedom.

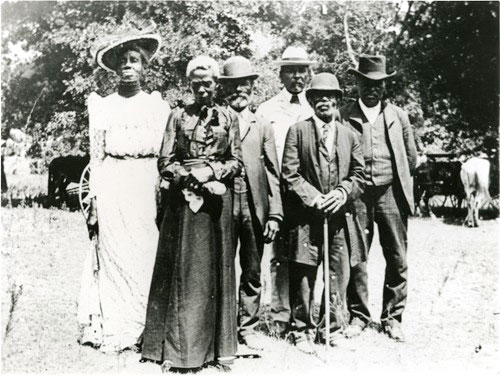

Starting in 1866, black Texans commemorated Juneteenth over generations in what became prominent outdoor events involving speeches, parades led by black cowboys on horseback, and picnics with signature Texas barbecue. As historian Elizabeth Hayes Turner pointed out, while white Texans built monuments to the state’s slave past, African Americans observed Juneteenth as a counter narrative to the glorification of the Confederacy, and a tribute to black equal rights. During the great migrations, Texans moved to West Coast cities Los Angeles, Bakersfield, Oakland, and Sacramento, bringing Juneteenth with them. By 1980, through the efforts of African American state legislator Al Edwards, Texas fittingly became the first state to declare Juneteenth a state holiday. In 1994, a movement developed to recognize Juneteenth as a national holiday.

Currently, forty-seven states acknowledge Juneteenth. In 2003, California’s legislature passed a resolution recognizing Juneteenth, and today, it’s hard to find a city in California that doesn’t offer public Juneteenth events, all different, but sharing two features based in history – barbecue, and a celebration.